'Her willing sacrifice': Love and Desire in Robert Eggers' Nosferatu

A Lacanian approach towards understanding the film's major themes

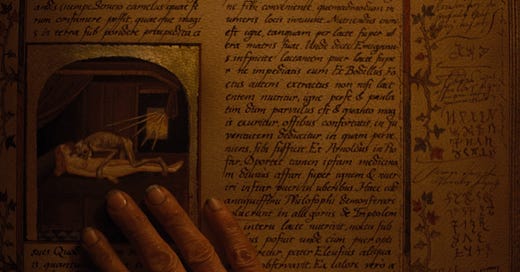

Robert Eggers’s remake of F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror, the second screen adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), is mostly a surprisingly faithful and beautiful homage to the 1922 silent film. Where the film particularly weaves its own path and develops the storyline further, however, is putting Ellen Hutter centre-stage, with her internal landscape and psychic connection to Count Orlok becoming the true foundations of the unfolding action.

In one of the interviews regarding her exceptional role as Ellen, Lily-Rose Depp discussed the emotional landscape of the character and explicitly declares how she perceives the story to be a “love triangle” of sorts:

“It is a love story with Count Orlok as much as it is with her husband. There’s a real love triangle there. Rob [Eggers] wanted there to be a palpable sensuality between [Ellen] and [Count Orlok]. And I think that serves the story as well, because it is so much scarier to think that there is a yearning between the two of them rather than just being this woman who’s chased down by a scary demon that she hates.”

It is an interpretation of the emotional dynamics in Nosferatu that shows up in various reviews and commentaries on the film. I think this is a somewhat simplified approach that blurs the boundaries between love and desire, while failing to give a satisfactory justification for Ellen’s attraction towards Count Orlok per se. Perhaps a brief exploration of Jacques Lacan’s (and Zizek’s) work could shed light on what’s truly at stake here.

Living in 1830s Germany at the dawn of first-wave feminism and the New Woman phenomenon (factors that influenced Bram Stoker himself while writing Dracula), it is sensible to attribute Ellen’s loneliness not only to personal eccentricities, but also to the social and cultural contexts her subject is embedded in. She yearns for a Real that is not attainable in her reality because of the symbolic and imaginary concealing of such Real by her language, her existence as a speaking subject. The nearest that Ellen and her husband Thomas come to experiencing the Real is, paradoxically, through their dreams, when they jolt from their nightmares at the point of the symbolic slipping the Real through its grasp, when the true nature of Count Orlok is (almost) revealed. The external restraints imposed upon Ellen’s womanhood do not suppress desire, but actually sustain and incentivize it.

It is undeniable that the question of libido is central to understanding Ellen’s attraction to Count Orlok. However, Ellen’s desire is not merely a bodily instinct; it is a sexual drive, and by ‘drive’ we mean a manifestation of desire that repetitively circulates around its goal but never attains it (think of how Ellen’s dreams and sleepwalking halt temporarily upon marrying Thomas but return eventually). This sexual drive, typically regarded as a life force, is mythologized by Lacan as a phantom being, an organ that “the organism's being takes to its true limit, which goes further than the body's limit […] This lamella is an organ, since it is the instrument of an organism. It is sometimes almost palpable [comme sensible], as when a hysteric plays at testing its elasticity to the hilt.” The palpable sensitivity that Depp mentions in the interview isn’t only portrayed in the physical interaction between Ellen and Orlok, but also in Ellen’s hysteria and ailment: Her epileptic fits, tearing down her garments, sweating profusely, ‘congested with blood’, with the amoebic phantom of libido that attempts to flow beyond the bodily constraints.

We can clearly see and articulate that the drive is not concerned with biological functionality, but with following its own aim all the way towards destruction. To Lacan, “every drive is virtually a death drive” because every drive pursues its own extinction and involves its subject in a compulsion to repeat.

Again, Lacan clearly states that:

“Speaking subjects have the privilege of revealing the deadly meaning of this organ, and thereby its relation to sexuality. This is because the signifier as such, whose first purpose is to bar the subject, has brought into him the meaning of death. (The letter kills, but we learn this from the letter itself.)”

Eggers’s Count Orlok (played by Bill Skarsgard) works perfectly as a signifier of Death; he’s visualized in the film as an ‘undead’ corpse instead of an attractive human philanderer or even an actual monster, as some previous cinematic iterations of the story have envisioned him.

Zizek draws an illustrative example in The Plague of Fantasies:

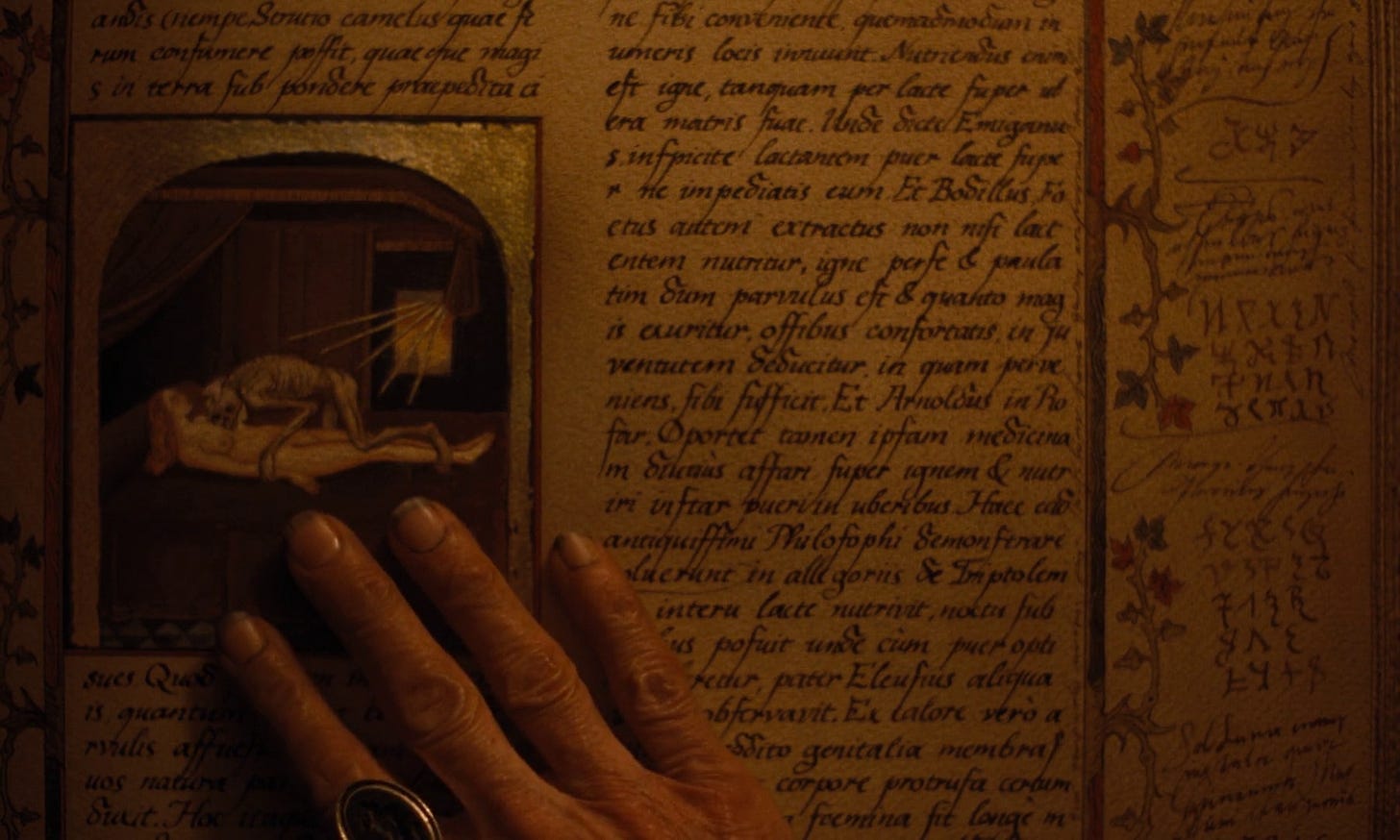

“It is as if we are not fit to fit our bodies: drive demands another, 'undead' body. The Unputrefied Heart', a poem by the Slovene Romantic poet France Prdferen, perfectly expresses the partial object of drive which is libido: years after a poet's death, his body is excavated for some legal reason; all parts of his corpse are long decayed, except the heart, which remains full of red blood and continues to palpitate in a mad rhythm - this undead organ which fellows its path irrespective of the physical death stands for the blind insistence; it is drive itself, located beyond the cycle of generation and corruption.”

It is important to note here that any desire faces an intrinsic impossibility of its full satisfaction, for a complete satisfaction can only be achieved when our interaction with the object of desire is bare, without any imaginary or symbolic facades, without language and speech. As our subjective beings are always structured around a lack of sorts (Ellen’s lack of connectedness and companionship stimulates her desires), it becomes the central locus of our desires, not simply to fill our lack but to find that lack in the Other.

We can note the problem that emerges here: You can only find that lack, that nothingness desirable when it is covered by a veil of imaginary and symbolic meanings, when it is not the Real outright. Not only would the sublime Real faced bare be, as Lacan puts it, an ugly “gift of shit” (Count Orlok is much more alluring as a shadow behind curtains than as a decaying physical presence), but it would also necessitate physical death, as the dissipated tension of dissatisfaction would completely crumble the entire system of human drive and desire.

This is where the concept of jouissance deserves recognition. It is clear that Ellen’s desire goes beyond the simple pleasures of domesticity and parenthood, pleasures that are constrained and bound by moderation and societal laws. Because any transgression of the laws in pursuit of a desirable object risks failure and could be experienced as pain (e.g. S&M) and suffering (Ellen’s connection to Orlok takes a huge physical and mental toll on her), pleasure becomes a conservative term that anchors itself in rational judgement and consequentialism.

Jacques-Alain Miller states that jouissance is “a certain destruction, and precisely in this it differs from the pleasure principle […] The very name jouissance fundamentally translates what resists the pleasure principle's moderation.”

It is because of jouissance that Ellen’s drive is a death drive. Ellen does not simply seek physical pleasure, nor is she oblivious to the spectre of death haunting her, it is precisely because Orlok promises a final demise that he becomes so desirable, by going beyond pleasure and violating norms and prohibitions that the release of death becomes ever so sweet, the closest one could get towards full satisfaction.

This is the only domain through which the connection between Ellen and Orlok becomes tangible and sustainable:

“This paradox of moving statues, of dead objects coming alive and/or of petrified living objects, is possible only within the space of the death drive which, according to Lacan, is the space between the two deaths, symbolic and real. For a human being to be 'dead while alive' is to be colonized by the 'dead' symbolic order (Ellen); to be 'alive while dead' is to give body to the remainder of Life-Substance which has escaped the symbolic colonization (Orlok). What we are dealing with here is thus the split between […] the 'dead' symbolic order which mortifies the body and the non-symbolic Life-Substance of jouissance.”

We can now, justifiably and confidently, inspect the dynamics between Ellen and her husband Thomas and contrast them to those between her and Count Orlok. More pertinently, it seems relevant to see the nuanced differences between desire and love through the Lacanian lens. It would be wrong to assume that Ellen loves but does not sexually desire Thomas (she clearly desires his physical intimacy). It would also be understandable to believe that Ellen has some capacity for love towards Count Orlok (a love towards a shared eccentricity, his distinct Otherness, a necrophiliac instinct?). Nevertheless, it is grossly inaccurate to think of the phenomena as interchangeable. When Count Orlok encounters Ellen at the Harding estate, he does not remonstrate against her defiant claim that he is incapable of love, rather establishing his motives solely in the realm of desire: “I cannot [love]. Yet I cannot be sated without you.”

The idea that love is metaphor and desire is metonymy is prominent in Lacanian analysis. Metonymy replaces one word with another that is closely related to it. The two words, two signifiers, establish a direct signifier-to-signifier connection. According to Lacan, since desire is always the desire of the Other, a desire for what is not satisfied or owned, it is “caught in the rails of metonymy, eternally extending toward the desire for something else.”

This is why Ellen, in her plea to the cosmic in the film’s opening scene, reaches out to "a guardian angel, a spirit of comfort... anything".

In contrast, the metaphor substitutes a word or a phrase with another that is unrelated and literally inapplicable. This substitution indicates that “a signification effect is produced that is poetic or creative, in other words, that brings the signification in question into existence.” Love is then the “metaphorical signifier [that] conceals the trauma (Real) which functions as the truth of the split subject’s symptoms (desires) and has the ability to dissolve it.” Ellen directly attributes the temporary cessation of her dreams to her loving relationship: “It all ended when I first met my Thomas. From our love, I became as normal.”

It’s evident that explaining love and desire in such a manner puts them in opposition to each other; Freud even went on to infamously say that excessive love kills desire and excessive desire kills love. Consider the conversation between Ellen and Thomas after leaving the Harding estate: After lamentations about Thomas’s decision to embark on his risky journey and unwittingly covenanting her to Orlok, Ellen provokes Thomas by telling him, “You could never please me as he could.” A shocking but earnest admission that is true not because Ellen and Thomas don’t love each other, but because they do. Thomas attempts to fend off the symbolic castration brought upon him by his wife’s condemnation and her desire towards the Other by engaging in a sexual act that fails to achieve jouissance.

It is a lose-lose situation: If the sensualist refuses "castration" (in this case, the loss of the specific object of his libidinal economy) by not surrendering his jouissance, then he loses both life and jouissance.

In the final sequence of the film, as Ellen repledges herself to Orlok, he declares that as “our spirits are one, so too shall be our flesh.” This is a Platonic perception of love in which the loved one, the object of desire, becomes at the lover’s mercy. “As the object of his desire the other’s only wish can be to incorporate me, i.e. to destroy me.” I would like to think that love could be based in difference, not as two severed beings forming a whole, but as one and the Other unconsciously locating their wounds in each other. Rather, it could be argued that Count Orlok is simply a material reflection of Ellen’s ego, and her sacrifice should be seen as a form of suicide.

References:

1. Jacques Lacan, Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English. 1966. Translated by Bruce Fink, New York; London, W.W. Norton, 2006.

2. Slavoj Žižek, The Plague of Fantasies. Verso Books, 5 Jan. 2009.

3. Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XI [ed. Jacques-Alain Miller; trans. Alan Sheridan], New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1977.

4. Jacques-Alain Miller, "Ethics in Psychoanalysis," Lacanian Ink, no. 5, Winter, 1992.

5. “On Lacanian Psychoanalysis: Death Drive, Reality, and Beyond.” 8 Jan. 2023, iambobbyy.com/2023/01/08/on-lacanian-psychoanalysis-death-drive-reality-and-beyond-2

6. Adrian Johnston, The Forced Choice of Enjoyment: Jouissance between Expectation and Actualization, https://www.lacan.com/forced.htm

7. Bruno Moroncini, On Love: Jacques Lacan and Plato’s Symposium. European Journal of Psychoanalysis, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2017.